Science Leads the Way: ISSF Publishes 2024 Annual Report Highlighting Scientific Achievements in Sustainable Tuna Fishing

The International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF) today released its 2024 annual report, Science Leads the Way, spotlighting the organization’s global efforts to drive sustainability in tuna fisheries through science-based solutions, industry engagement and policy advocacy.

With nearly half of ISSF’s budget dedicated to science in 2024, the report details a year rich with research milestones, collaborative partnerships and field-level impacts — efforts collectively aimed at ISSF’s ultimate objective: helping tuna fisheries to meet and maintain the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) standard criteria. From publishing the first “jelly-FAD” construction guide on biodegradable, non-entangling fishing gear to organizing 34 workshops for tuna fishers worldwide, ISSF continues to place science at the core of its efforts.

“ISSF uses the power of the scientific process to illuminate ways to continuously improve sustainable tuna-fishing policies,” Susan Jackson, ISSF President, remarks in the report. “In the big picture of fishery sustainability, solution-oriented science is essential for sound policy. Our research can have the most impact when RFMOs and government agencies are able to leverage it to enact optimal conservation measures for fisheries.”

Science Leads the Way reviews ISSF’s continued global collaborations, marine research projects and advocacy efforts to identify and promote best practices in tuna and ocean conservation with fishers, tuna companies and tuna regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs). The report also covers ISSF’s activities with peer environmental nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and scientific agencies and highlights its work to promote verified accountability in sustainability commitments across the tuna supply chain.

Jackson continued, “The work that ISSF is so fortunate to do depends on a global community — conservation-minded fleets, progressive seafood companies and retailers, persevering researchers, innovative manufacturers, dynamic NGOs, and committed RFMOs and governments — cooperating across continents to protect ocean resources.”

2024 Highlights from Science Leads the Way

- Electronic Monitoring Milestone: Support of RFMOs in adopting standards for fleets to use electronic monitoring (EM) — and providing resources to assist vessels in transitioning to EM technology. As of year-end, all four tropical tuna RFMOs have adopted minimum standards for EM use.

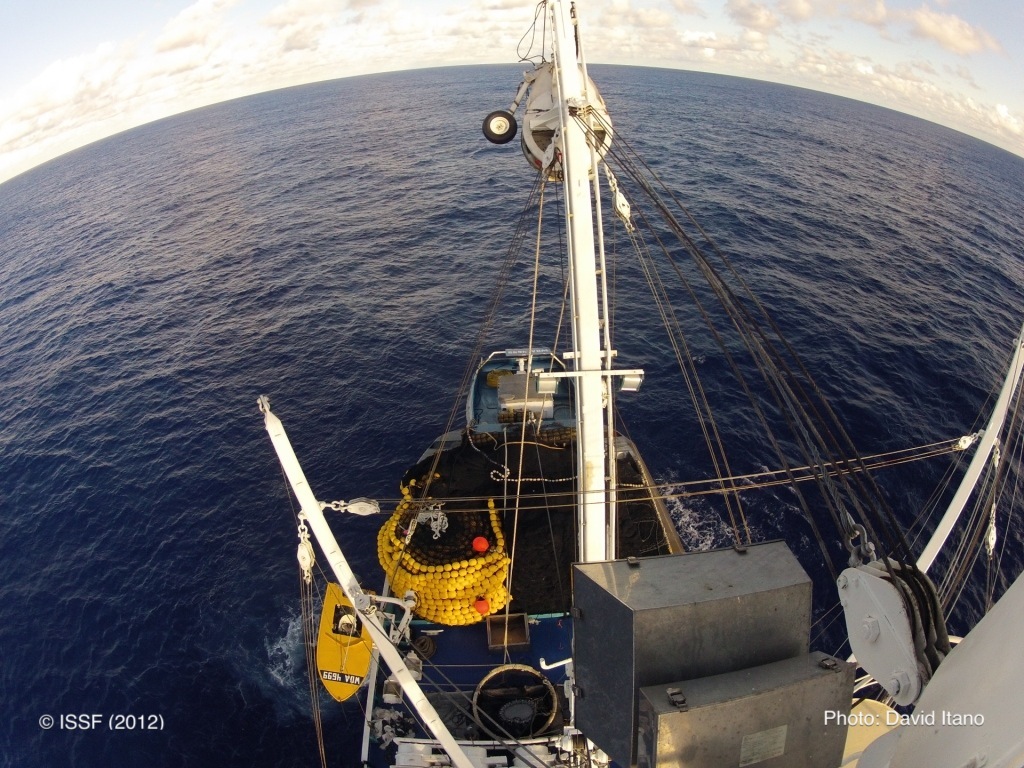

- Breakthrough on Jelly-FADs: The release of a fisher construction guide for building nearly 100% biodegradable FADs marks a key step toward reducing ocean plastics and bycatch risks.

- Scientific Output: Co-authoring 16 peer-reviewed journal articles and participating in 36 coordinated research projects and 56 RFMO meetings demonstrates ISSF’s robust scientific engagement and leadership.

- Supporting Sustainability Certification: Advancing MSC fishery certification and assessment processes for the world’s tuna fisheries by submitting 77 stakeholder submissions to 62 fisheries.

- In-the-field Outreach: 523 participants attended ISSF-organized or -supported fishers workshops, with sessions focusing on FAD retrieval, bycatch mitigation and best practices for longline fishers.

- Global Advocacy Alignment: Analysis of RFMO statements showed a 90% alignment between ISSF’s priorities and those of nearly 50 other environmental NGOs.

Driving Industry Accountability and Transparency

Science Leads the Way also highlights increasing tuna supply chain accountability through ISSF programs and tools for verified tuna company and fishing vessel transparency. As of year-end:

- The ProActive Vessel Register listed an all-time high of 1,739 vessel registrations, showing vessels of all gears and representing over 80% of the global large-scale purse-seine vessel fish hold volume. ISSF also reached 808 vessel registrations, a 63% year-over-year increase, on its Vessels in Other Sustainability Initiatives (VOSI) resource.

- 17 of 23 ISSF participating companies achieved full conformance with ISSF’s 33 conservation measures, verified through third-party audits and publicly reported on the ISSF website.

Explore the Interactive Report

Downloadable infographics, links to related reports, and interactive content on the ISSF website are also available throughout the Science Leads the Way PDF. The full 2024 annual report is available at iss-foundation.org/annual-report.