Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs)

In many ways, ISSF supports tuna Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) in following scientific advice to protect and conserve tuna stocks, reduce bycatch, and improve the health of marine ecosystems.

Tuna are highly migratory, swimming through both international waters and waters belonging to many nations. To manage tuna stocks, countries sharing these resources joined together to create RFMOs.

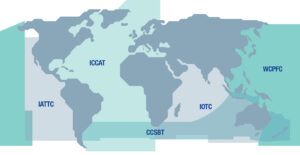

Five RFMOs worldwide oversee tuna fisheries management in their respective ocean regions. RFMOs have the legal frameworks, geographic scope, and membership to facilitate positive change across global tuna fisheries.

Member nations of these RFMO governing bodies are responsible for setting catch limits; monitoring stock health; and regulating data collection, on-the-water monitoring, and methods to mitigate fishing’s ecosystem impacts, among other issues.

TUNA RFMOS

The Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) is governed by the Convention for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna and is responsible for the management of southern bluefin tuna throughout its range.

The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) is governed by the Antigua Convention and is responsible for the management of tuna and tuna-like species in Pacific Ocean waters east of 150°.

The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) is governed by the ICCAT Convention and is responsible for the management of tuna and tuna-like species in the Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas.

The Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) was established under Article XIV of the FAO Constitution and is responsible for the management of tuna and tuna-like species in the Indian Ocean and adjacent seas, north of the Antarctic Convergence.

The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) is governed by the 1982 Convention and the Agreement (The Law of the Sea and UNFSA) and is responsible for the management of tuna and tuna-like species in the Pacific Ocean west of 150ºW to the north of 4ºS and waters west of 130ºW to the south of 4ºS.

Conservation Measures to Support RFMOs

Several ISSF conservation measures were established specifically to support RFMOs and their regional tuna fleets in following best practices — specifically in vessel registration, listing, and authorization.

RFMO ADVOCACY PUBLICATIONS

Position Statements to RFMOs

Every year, ISSF produces Position Statements for RFMOs in advance of their policy-making meetings — outlining our recommended topics for discussion and priority actions for sustainable fisheries.

RFMO Best Practices Snapshots

As part of our policy and advocacy work, ISSF evaluates tuna RFMOs' progress in implementing best-practice recommendations. Our "RFMO Best Practices Snapshots" (PDFs) cover compliance processes, IUU vessel listing, transshipment, and other fisheries management topics.

RFMO Priorities

ISSF’s science and advocacy experts share concerns and advice for RFMOs in 2024.

RFMO Best Practices Snapshots

Our "snapshots" benchmark tuna RFMOs based on best practices for sustainable fisheries management.

Regional Tuna Catches

The five largest tuna catches in tonnes are Western Pacific Ocean skipjack, Western Pacific Ocean yellowfin, Indian Ocean skipjack, Indian Ocean yellowfin, and Eastern Pacific Ocean yellowfin.

RFMO Infographics

In our infographics library, you'll find original ISSF graphics on key RFMO topics.