How Do We Minimize the Impact of Tuna Fishing on Manta and Devil Rays? Just Ask Fishers.

How do we protect vulnerable species from commercial fisheries? As it turns out, fishers themselves may have some of the best answers.

Manta and devil rays (together referred to as Mobulids) are an incredibly captivating group of large fish species and iconic ocean flagship species. However, these species are experiencing global declines due to accidental capture or “bycatch” in industrial tuna fisheries, including purse seine fisheries.

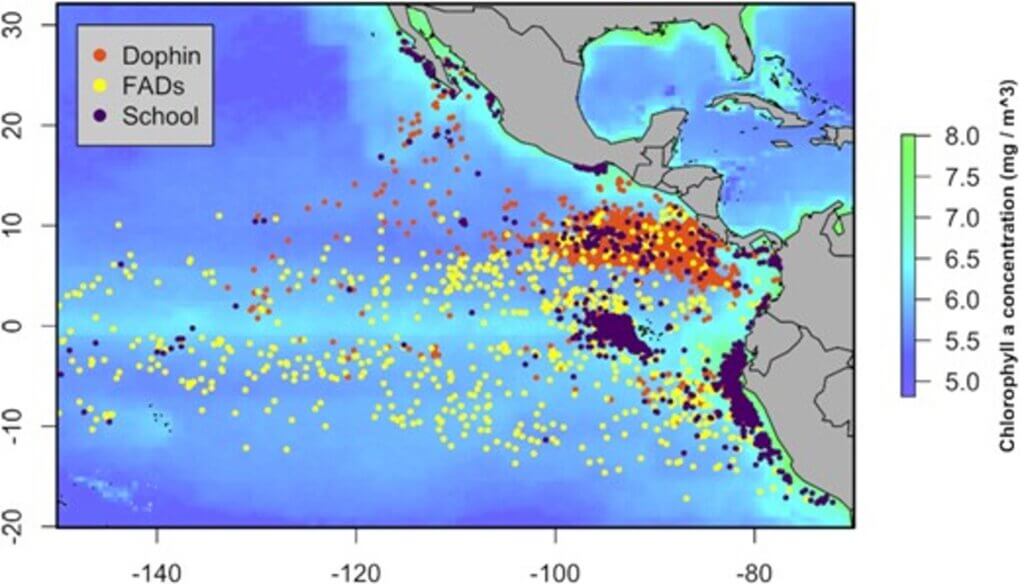

It’s been estimated that more than 13,000 Mobulids are captured each year by purse seine vessels, and this capture — combined with the bycatch of other tuna fisheries and other threats like wildlife trade for their gill plates, habitat degradation, and entanglement in other types of fishing gear — is driving population declines for these threatened species globally. In the Eastern Pacific Ocean, Mobulid bycatch by tuna purse seiners is decreasing despite increases in fishing effort in the region — suggesting that these populations may be in decline.

Fisher Observations & Insights

But there may be good news for manta and devil rays.

One recent study showed that improving handling and release methods for Mobulids would be effective for improving their status. In other words, improved practices during fishing operations in the tuna purse-seine fishery could provide serious conservation gains for these vulnerable species. But exactly what methods could reduce their capture and mortality — and how feasible these are onboard tuna vessels — wasn’t known.

To answer these questions, our team set out to learn straight from those with the most experience: fishers (i.e. captains, deckhands, and navigators) and fishery observers, who experience Mobulid bycatch firsthand.

Over the course of several months, we conducted surveys and focus groups with fishers and other stakeholders who had experience working onboard tuna vessels. We were excited to find that fishers have a huge cache of knowledge about Mobulids and how to reduce their capture and mortality.

One major finding was that Mobulids are more likely to be caught in free-school sets than in Fish Aggregating Device (FAD) sets. They also informed us that Mobulids are sighted by fishers after capture in the net but not yet onboard, suggesting that this is an important time where focused mitigation efforts can improve their chances of survival.

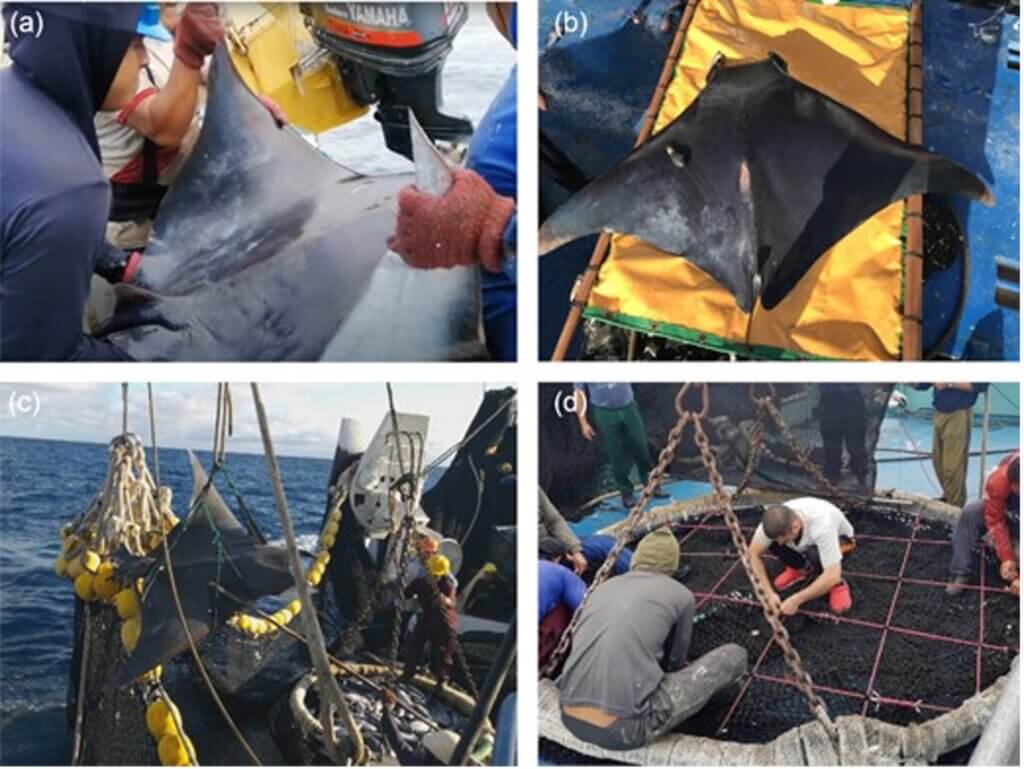

Other ideas brought forth by fishers include the use of homemade “manta grids” (photo below), modifying cargo nets and other onboard equipment, and the potential utility of helicopter pilots and spotters to help vessels avoid Mobulids even before fishing begins.

Bycatch Mitigation Challenges

But though fishers had novel ideas to improve bycatch-mitigation practices for Mobulids, they also identified important challenges that have prevented them from using these practices in the fishery.

One of these challenges was the difficulty of releasing large animals that are too heavy for crew to lift manually. Another was simply the lack of release devices necessary to remove Mobulids, which can be physically difficult to hold.

Fortunately, these obstacles could be solved by developing technology that utilizes existing mechanics onboard the vessel to hoist large animals and ensuring that these and other needed equipment are present on all purse seiners that encounter Mobulids.

We also noticed that captains and officers are more likely to be surveying the sea from the vessel deck or the crow’s nest — rather than focused on tasks on the deck — and so more likely to see a Mobulid prior to capture. The fact that these more senior “managerial” crew may identify Mobulids earlier is promising, as, generally, only managerial crew can request to stop fishing operations so that Mobulids can be quickly released.

Collaborative Research Continues

The results of this study were recently published in the journal ICES Journal of Marine Science for a special issue about bycatch, and are the latest update in an ongoing collaborative project funded by the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, involving researchers from University of California, Santa Cruz; TUNACONS; the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission; the Monterey Bay Aquarium; and Manta Trust.

Beyond providing practical knowledge about how fisheries can protect Mobulids, this study offers a model of a collaborative approach that harnesses fisher and stakeholder perspectives on bycatch mitigation and the conservation of vulnerable species. Next, our team is working to expand the findings of this work through real-world trials of some of fishers’ ideas. Stay tuned for more as we work together to protect iconic manta and devil rays.

Doctoral student Melissa Cronin of the University of California, Santa Cruz, was the Grand Prize winner in ISSF’s International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF) Seafood Sustainability Contest. She won for her contest entry, “Incentivizing Collaborative Release to Reduce Elasmobranch Bycatch Mortality,” which proposed handling-and-release methods that purse-seine vessel skippers and crew can use to reduce the mortality of manta rays and devil rays incidentally caught during tuna fishing. Ms. Cronin is a Ph.D. candidate in the Conservation Action Lab at UC Santa Cruz studying Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.